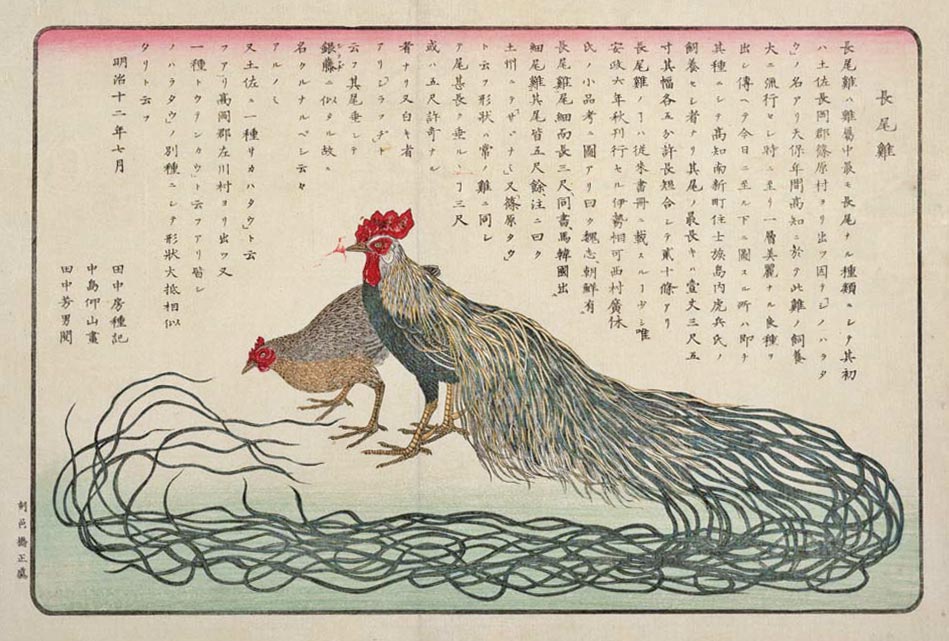

江戸末期から明治初期に日本を訪れた欧米人は、3m を超える尾羽をもつ鶏の存在に目を見張ったに違いない。極東の珍しい物産が盛んにヨーロッパに送られているなかで、尾長鶏も驚きの生き物としてヨーロッパに送られた。レグホーンやミノルカなど多くの鶏の品種名には、積み出された港町の名が付いている。矮鶏はヨーロッパにもたらされた時代にはナガサキと呼ばれ、尾長鶏はヨコハマの名で呼ばれていた。

私の手元にある1972 年版ギネスブック動物編の写真は、着物姿の人が手に尾長鶏を止め、伸ばした尾羽の先をかすりの着物の少年が支えているものである。最も長い尾羽をもった鳥類として紹介され、尾羽の長さは20 フィートすなわち7m ほどと記載されている。尾長鶏の尾羽は天保年間の1830 年代に3m だったとされ、シーボルトが見たとすれば3m 級だったであろう。明治中期に4m、昭和初期に8m となったとされるから、ギネスブックの写真は大正後期から昭和初期のものと推定することができる。尾羽が10m を超したのは戦後のことで、現在までに13.5m に達したものが創られている。

尾長鶏は突然変異で尾羽が換羽しない鶏を選抜して成立した。当時は育種という学問があったわけではないが、飼育していた農民は尾羽の換羽しない鶏を選び、大事に育て殖やしていたと想像することができる。尾長鶏は生物学的な育種方法だけで作られたわけではなく文化的な背景が支えになって創られた。参勤交代の際の、土佐藩主山内候の大名行列の先頭を行く槍の鞘飾りに尾長鶏の尾羽が使われ、評判になっていた。土佐藩では長い尾羽を提供した農民には褒美をあたえ、飼育を奨励していたのである。尾長鶏の存在は土佐藩の秘密事項であり、存在が知れたのは江戸後期のことといわれている。

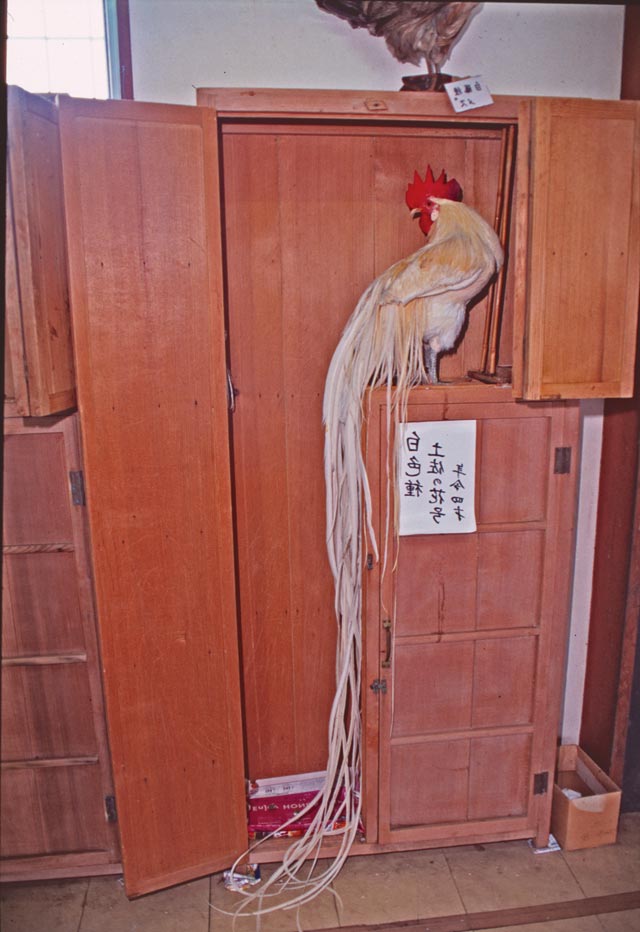

尾羽の長い雄鶏は止箱とよばれる飼育箱で飼われ、運動には尾羽が脚に絡まないよう、束ねた尾羽を人が持ちながら付き添う。尾羽は1 年に1m 前後伸びるが3 歳と5 歳のときに換羽しやすく、この時期を超えれば10m 級になる。雌鶏は換羽するので尾羽は伸びない。雄鶏は雌鶏といっしょに平飼いにすると尾羽は擦り切れてしまうので、繁殖には尾羽の伸びのよい雄鶏と同系統の雄鶏を使う。長い尾羽を伸ばした雄鶏の兄弟鶏が次代を担う種鶏の役を果たすのである。

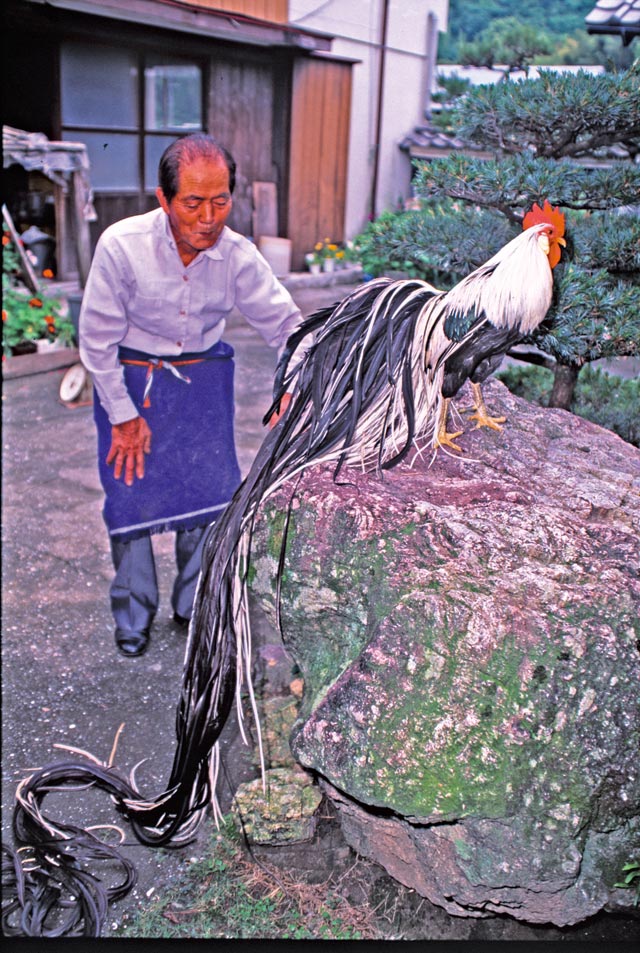

20 年ほど前、南国市大篠長尾鶏保存会に田島正則会長を訪ねたことを思い出す。特別な日本鶏、見方によっては奇異な品種をたくさん作出した土佐の地に行ってみたい、土佐の風土を感じてみたいという思いが実現したときのことである。最初に高知県畜産試験場に尾長鶏の研究者である平岡英一先生を訪ね、土佐の日本鶏についてお話を伺った。試験場内で東天紅、小地鶏、鶉尾、尾曳などいろいろな土佐由来の日本鶏を見せていただいたが、尾羽の長い尾長鶏は飼われていなかった。

天然記念物に指定されている日本鶏17 品種のうち5 品種が土佐の地で作出されたもので、尾長鶏は1923 年(大正12 年)に「土佐ノ尾長鶏」の名称で天然記念物指定された。1952 年(昭和27 年)に特別天然記念物に昇格したときは「土佐のオナガドリ」と名称変更されている。土佐地鶏ともよばれる小地鶏はニワトリの原種であるセキショクヤケイの羽色とそっくりな古代のニワトリの面影を受け継いでいる。東天紅は新潟の蜀鶏(唐丸)、秋田の声良とともに長鳴き鶏として有名で、25 秒の時を告げた記録もある。

鶉尾と尾曳は鶉矮鶏、蓑曳矮鶏ともよばれるが、矮鶏ではなく小地鶏から作出された小型鶏である。尾曳は尾羽が長く小型尾長鶏と言ってもよいような風情がある。一方、鶉尾は尾骨が無く尾羽の生えない、言わば尾曳や尾長鶏の対極のニワトリであり、腰の蓑羽が下半身を円く包み愛らしい。

平岡先生にご案内いただき、田島会長をお訪ねし、尾羽の長い田島さんご自慢の尾長鶏に会うことができた。田島さんは止め箱から白藤の美しい尾長鶏を出してくれ、海鼠壁を背景に大きな岩の上に止まらせてくれた。80 歳を超えている田島さんは、前屈みの姿勢で束ねた尾羽を抱えてオナガドリに付き添い歩き運動させるのを日課とされていた。骨の折れる地道な仕事であり、土佐人の根気の良さが伝わってきた。根気、熱意、そしてわずかな変異を見逃さない観察眼、新しい品種を創りだそうとする好奇心が、様々な日本鶏を作出させた風土で育まれ続けてきたに違いない。

田島さんは後継者難を嘆かれていたが、これほど根気のいる飼育を志す若い人はなかなか出てこないのも道理である。保存会で一番若い人は50 代だそうで、田島さんはにやりとして「実は私の息子ですが」と教えてくれた。今年は酉年、世界に誇れる土佐の宝が、日本の遺伝資源として、日本の生ける文化財として、いつまでも継承されることを願いたい。

Onagadori (Long-tailed chicken)

The Westerners who visited Japan from the end of Edo period to the early Meiji period, must have been amazed by the chicken with the long tail feathers reaching over 3 m. As one of the many unique products that were sent to Europe from Far East, Onagadori was sent to Europe as an amazing living creature. Many of the chicken breeds such as Leghorn and Minorca were named after the ports where they were shipped from. Chabo (Japanese bantam) used to be called Nagasaki when they were sent to Europe for the first time, and Yokohama for Onagadori. I have a book of Guinness World Records by animals issued in 1972, and there is a picture of Onagadori held by a man in kimono and the tail end by a boy. It was introduced as the bird with the longest tail feathers which were 20 ft (7 m) in length. The tail feathers of Onagadori used to be 3 m in 1830s, and if Siebold was there to see it, it would be about that size.

The tail feathers length was up to 4 m in the middle of Meiji period, and became 8m in the early Showa period, so the picture of Guinness book should be taken between the end of Taisho and the early Showa period. It was after the war when the tail’s length exceeded 10 m, and has reached 13.5 m at the longest to date. The Onagadori induced from selected chickens whose tail feathers don’t molt by mutation. There wasn’t a study of inbreeding at that time, but I can imagine that farmers selected the chickens with non-molting tails and raised them carefully. Onagadori wasn’t induced with just biological inbreeding methods, but also with the support of cultural background. During a journey to Edo for an alternate year attendance, the leader in the Daimyo’s procession of Lord Yamanouchi of Tosa domain adorned the sheath with Oganadori’s tail feather and that became popular. In the Tosa domain, farmers who provided the long tail feathers were rewarded and breeding was encouraged.

Onagadori was a confidential matter in Tosa domain and they came to be known at the end of Edo period. Male birds are kept in the rearing cages called Tomebako, and accompanied by people who hold the tied tails to prevent them from tangling in their legs when they exercise. The tail feathers grow about 1 m per year and more likely to molt at the age of 3 and 5, but they grow to about 10 m if they past that period. Tails of the female birds don’t grow because they molt. Keeping the male birds with female birds in openspace breeding will cause the tails getting worn out, so male birds with long tails in the same group are used for breeding.

Siblings of long tailed male birds fulfill a role of breeding hen for the next generation.

I remember visiting a Chairman Masanori Tajima at the reservation society of Oshino Onagadori in Nangoku city about 20 years ago. I had always wanted to visit Tosa where a lot of special Japanese chicken breeds, some may look unusual, are bred and feel the cultural climate. First, I visited Dr Hidekazu Hiraoka who studies Onagadori at the live stock experimental station in Kochi prefecture and heard the story about Japanese chicken in Tosa. He showed me a variety of Japanese chicken originated in Tosa such as Totenko, Ko-jidori, Uzurao and Ohiki, but Onagadori with long tail wasn’t there. Out of 17 kinds of Japanese chicken which are designated as natural treasure, five of them were induced in Tosa. In 1923 ( Taisho 12th), Onagadori was designated as natural treasure and in 1952 ( Showa 27th), it was promoted to special natural treasure. Ko-jidori, also called Tosa-jidori inherited the feather color from ancient chicken Red junglefowl and features from ancestral chicken.

Totenko is Tomaru of Niigata prefecture and with Koeyoshi of Akita prefecture, both are best known for their exceptionally long crows, which can be sustained for up to 25 seconds.

Although Uzurao and Ohiki are also called Uzura-chabo or Minohiki-chabo, they are not chabo (bantam) but actually are small chicken bred from Ko-jidori. Ohiki have long tails and look like small Onagadori. On the other hand, Uzuraoposite don’t have tailbone or tail feather, so to say directly op of Ohiki and Onagadori, but the way feathers in the back wrap the lower body look charming. Dr Hiraoka guided me to see Chairman Tajima and there I saw the Onagadori of which he is proud. Chairman Tajima brought a beautiful Onagadori out from a box and put it on a big rock in front of the walls covered with square tiles jointed with raised plaster.

Chairman Tajima, who was over 80 years old, slouched along with the bird holding its tail feathers everyday for exercise.

It is a hard painstaking job and I felt the patience of people in Tosa. Patience, enthusiasm, power of observation, which don’t miss any changes, and curiosity for creating new breed must have been nurtured in this climate where a variety of Japanese chicken were bred. Chairman Tajima mentioned a dif ficulty of having a successor, and I understand the difficulty of finding a young person who wants to take the hard painstaking job. The youngest person in the reservation society is in his 50’s. Mr Tojima smiled and told me that was his son. This is the year of the chicken, and I hope our worldclass treasure of Tosa will always be inherited as Japanese genetic resource as well as living cultural property of Japan.

小宮輝之(こみや・てるゆき)

1947 年、東京・神田生まれ。明治大学農学部卒業。1972 年に多摩動物公園の飼育係として動物園人生をスタート。2004 年から2011 年まで、上野動物園史上唯一の“飼育係出身”園長を務めた。昨今は大好きな動物園・水族館めぐりの傍ら、どうぶつの足跡を採集する「足拓墨師」としても人気を博す。『あしあと動物園』など著書多数。

Teruyuki Komiya

Born: 1947 in Kanda, Tokyo. Studied Agriculture at Meiji University. Started

his career in zoo world as a keeper at Tama Zoo in 1972. He served as the first director promoted from a keeper from 2004 to 2011. Recently, he has become popular for the animal ink footprint artist that he collects as he visits

zoos and aquariums, also nature. He has published many books such as his